Hard science fiction: is it actually a coherent subgenre or is it just an arbitrary body of work defined nebulously enough to facilitate gate keeping? On the one hand, I claim to be a fan of the stuff so it sure would be handy if it actually existed. On the other, a lot of works marketed as hard SF have features like psionics, faster than light travel, and an Earth spinning in the wrong direction1 that seem pretty hard to reconcile with actual science.

Still, I think there’s a gap between hard SF defined so narrowly only Hal Clement could be said to have written it (if we ignore his FTL drives) and hard SF defined so broadly anything qualifies provided the author belongs to the right social circles … that this gap is large enough that examples do exist. Here are five examples of SF works2 that are, to borrow Marissa Lingen’s definition:

playing with science.

and doing so with a verisimilitude that’s not just plot-enabling handwaving.

Mary Robinette Kowal’s alternate history space colonization epic Lady Astronaut of Mars series (The Calculating Stars, The Fated Sky, The Relentless Moon, and The Derivative Base) is pretty uncontroversially hard SF. The event that kicks the overarching crisis into action, a meteor impact that threatens the terrestrial ecosystem, is straight out of paleontology3 . The gratuitous racism and sexism against which the protagonist contends is straightforward human sociology (and history). The means used to reach Mars is literal rocket science. The series couldn’t be harder SF if Kowal had a slide rule and a lifetime membership in the British Interplanetary Society.

Before Kowal sent her characters to Mars, there was Maureen F. McHugh’s ambitious China Mountain Zhang, Her 22nd century world is one dominated by China, one where the future is, to borrow a phrase, unevenly distributed. For most people, freedom is possible only if one can avoid official notice. McHugh’s setting is more technologically advanced than ours. For its characters, it is simply their mundane world. Just as our world might seem marvellous to someone from the early 1900s but unremarkable to us.

Lee Killough’s A Voice Out of Ramah may feature some improbable props like interstellar teleportation gates, but the plot itself is driven by biology. Specifically, it’s driven by the question of how it could be that a population exposed to a disease that kills most but not all of the men has failed to select for a population entirely immune to the disease. To the protagonist’s increasing horror, the explanation is quite simple: of course the disease has selected for immunity, but since the people running the society believe limiting men to a small ruling elite is socially beneficial, the powers that be randomly poison most of the boys at puberty. This is revealed near the beginning of the book: the plot centres on the outcome of this revelation.

In Linda Nagata’s The Red series (First Light, The Trials and Going Dark), computer technology transforms warfare. Not only are individual soldiers enhanced, and not only are drones and autonomous weapons important features of the battlefield, but increasingly powerful, insidious algorithms play a growing role in how the new military forces are used. The AI, the Red, is arguably as intelligent as humans although the alien nature of its thought processes makes that difficult to determine. It’s definitely adept at using humans to accomplish its goals, despite the attempts of the puny humans efforts to retain autonomy.

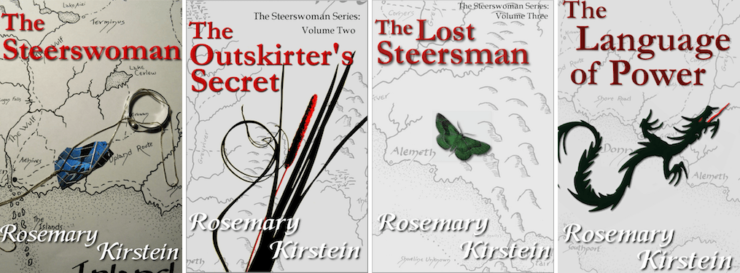

Of course, the best example of hard science fiction to date is Rosemary Kirstein’s Steerswoman series (The Steerswoman, The Outskirters’ Secret, The Lost Steerman, and The Language of Power). What at first appears to be a straightforward fantasy setting, in which wise-woman Rowan finds herself pitted against a community of (generally quite disagreeable) wizards, is soon revealed to be nothing of the sort. In fact, Rowan’s world is far more alien and interesting than most secondary-world fantasies. Rather than a Tolkienian struggle between good and evil as such, the heart of the series is science itself, the process of unravelling the true nature of the world despite all the barriers placed in our way. Those barriers might include the disconnect between human intuition and reality, or an intransigent ruling classes determined to monopolize knowledge. The series is a remarkable one, whose only flaw is the deliberate pace at which new volumes come out: four volumes since 1989.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.

[1]But what of egregious violations of the laws of thermodynamics, you ask? Surely there will be a gratuitous dig at Sundiver’s “cooling lasers”? I think Sundiver is space opera and alas, basic thermodynamics often does not apply to space opera. At least the novel does not have anyone using passively reflected light to heat an object up to a temperature hotter than the light source.

[2]I believe it is also useful to talk about hard fantasy, but that’s a different essay.

[3]The impending climate change seems implausible to me, but given that the book is set in the 1950s, when climate models and the tools to play with them were far more primitive, it’s quite possible that our heroes just figured wrong.

[undefined]undefined

I’m glad that you included China Mountain Zhang. McHugh’s book profoundly influenced my own thinking… and writing!

Joan Slonczewski should be on this list. The sequels to A Door into Ocean are chock full of hard as nails genetics, alien echosystems and inventive xenobiology.

Cooling lasers are, in fact, theoretically possible. They would use a heat gradient for the generation of photons, which are then sent away from the object to be cooled. Mind you, Brin is talking several orders of magnitude beyond what the article I linked discusses and I only know about it through him crowing on his blog, but it probably isn’t a violation of the laws of thermodynamics.

Robert L. Forward’s Dragon’s Egg is my go-to book for defining “hard science fiction”. But on the other hand I haven’t read any of the ones you mentioned, so I could be wrong. :) The Steerswoman series seems kind of reminiscent of Chalker’s Soul Rider series: Things start off being presented as straight-up magic, but gradually you see under the covers to find out it’s the highest of high-tech matter and energy manipulation & neural computer interfaces.

Thanks for this list! I will have to dive in.

p.s. in Footnote 3, I believe you meant to write impending/?

@5 – Fixed, thanks!

My definition is similar, in that the science needs to be integral to the plot. To that note, China Mountain Zhang may not qualify, since it’s the personal and social struggles, not the science, that drive the story.

On the flip side, I consider much of C.J. Cherry’s work hard science fiction because the plots are driven by science, but usually they’re what are called “soft” science: anthropology, sociology, psychology.

To help with definitions: I usually allow one big unlikely thing (FTL, terraformed or earthlike worlds, Wil McCarthy’s neubles, Vernor Vinge’s bobbles), so long as it’s used consistently. Psionics isn’t a deal killer, but if you say, “Because people were living in space, psionics spontaneously arose” (see Gundam) you’ve drifted into space fantasy.

Is the only one of these with cover art that is at all interesting and sells the book, too.

@8 The art’s ok, but for me the description sold it. It reminds me of a cross between John M Ford and Lois McMaster Bujold. Just ordered from Amazon.

I’ll second @7 Joel Finkle’s idea of what I’ve always called a “gimme” not disqualifying a story from being hard SF. The canonical gimme being FTL. Without it, stories about far off planets can’t be told. (Or can’t be told without the “long view” anyway.)

I’ve been considering the idea that science fiction isn’t a genre at all, but a platform. Within that platform are many genres: mystery SF, romance SF, horror SF, action SF, psychological SF, and so many more.

Perhaps SF hardness is also a platform attribute more than a genre attribute.

Someone once said that (in a story), if I blink my eyes and transport across the galaxy and explain the mechanism (or even indicate there is a mechanism), it’s SF. Absent the mechanism or explanation, and it’s fantasy. Perhaps SF hardness can be related to the degree of explanation or mechanism? (And perhaps to the degree the explanation accords with physics as we know it?)

If we’re too restrictive about defining it, we end up with science stories. The whole point of SF is to extrapolate current reality to something new.

Clarke’s Third Law seems to apply along with stories that seem like fantasy but turn out to be based on technology (McCaffery’s Pern series was my first exposure to that sort of thing). The Flying Sorcerers (Niven and Gerrold) plays with this, too…

@@@@@#4 theclapp: You mentioned Chalker’s Soul Rider series. I thought exactly the same thing when I read the description of Kirstein’s Steerswoman series, which I’ve not read either.

This no longer surprises me. A year or so ago I accidentally (and happily) ended up in a reading by Wesley Chu from his Lives of Tao novel. During Q&A my first question was “Have you ever read Clement’s Needle?” Wesley kind of ducked a little as, though he had never read the novel, I wasn’t the first person to ask him that question.

He told me he’d read it, and I promised that I wasn’t being critical of his work by asking the question, I was just curious about influences. Been around long enough, you’re going to see new stuff that at leastt superficially resembles old stuff.

Kirstein’s series is fairly comprehensively unlike anything by Chalker.

@11,@12: The Steerswoman books could not be less like Chalker to save their lives.

How about the stories about systematizing magic like Pratt and DeCamp’s Harold Shea series or Rick Cook’s Wiz Zumwalt series?

Joel Fritz, #14:

How about the stories about systematizing magic like Pratt and DeCamp’s Harold Shea series or Rick Cook’s Wiz Zumwalt series?

See Footnote 2, above.

I see what you did there with having an all-female list and not drawing attention to it, much like the thousands of all-male lists didn’t mention being all-male. Very nice, whether it’s deliberate or not.

In fairness, a lot of hard sci fi has fallen victim to Science Marching On. As far as psionics goes, at one time there was still semiserious research into psychic phenomena; Rhine cards and all that sort of thing. And John W Cambell was a big beleiver in the idea that it would produce positive results any day now, so lots of psionics stories got put in Astounding and here we are.

Hardness in SF is rare Some non-hard SF is the best work in the field, so it is not a criticism of the works on your list that none of them are hard SF. It IS a criticism of your list.

The subscribe link is borked. It just links back to this page, there is no subscription code behind it.

@18: To be fair, today’s hard SF will be tomorrow’s fantasy. There’s no way around it.

@2: I heartily agree. I just wish Slonczewski would churn out more of them.

Weird: subscribe worked for me when this first went up :(

I’m fairly sure that about two thirds of Greg Egan’s output qualifies as “playing with science”. The only problem is that you have to be at the very least addicted to good science popularizations to stand a chance of enjoying it…

I was able to subscribe later after I did a “reload with no caching.” OK, I did get four separate notifications that there were new messages, but maybe one of the admins was trying really hard to subscribe me?

All is well now. Probably.

“it’s the highest of high-tech matter and energy manipulation & neural computer interfaces.”

That fits the anime Scrapped Princess (hints start dropping in episode 2 so I don’t regard this as a spoiler); there’s so much ancient clarketech flying around that it’s disconcerting to find something powered by D-T fusion.

Kirstein’s tech is much more grounded. It’s not entirely “we could do this today with heroic engineering” but it’s not far from that.

#theclapp #steve davidson

The Steerswoman Series is nothing like what you think. There’s a reason why it is included in the really Hard SciFi list. Saying anything more would be a spoiler, but do look it up. It’s definitely a lot more than fantasy-becomes-whatever

Why would you write an article about hard science fiction without even one sentence defining what it is? Your article has a wider distribution than just loyal fans. Anyway, thanks for the great suggestions!

To add to what has been said about laser cooling, it is not only theoretically possible, but an actual technique that is often used. It relies on the Doppler effect, where a laser is precisely tuned to an absorption line for a molecule traveling towards the laser. Once absorbed, due to conservation of momentum, the molecule is now moving more slowly. The molecule then reemits a photon (to reach ground state again), but due to its slower velocity (and here’s where the Doppler effect plays in), the emitted photon is at a slightly higher frequency then the one absorbed, thus the molecule has slightly less kinetic energy than before and has “cooled”.

@28: In that case, the laser is used to cool molecules external to the laser. In the Brin book (as I recall), the laser cools the spaceship that the laser is attached to, by using the laser to transmit energy into the Sun.

#27: ‘Here are five examples of SF works that are, to borrow Marissa Lingen’s definition: playing with science.’

There’s your definition.

And yeah, the “laser cooling” of small atoms in the lab is nothing like the “laser cooling” of Sundiver, which is doing the job of an air conditioner, badly. Why use a laser rather than a blackbody radiator hotter than the sun? The point of heat removal is to remove entropy and lasers are low entropy; someone once compared Brin’s idea to cooling your house by throwing ice cubes out the window.

I always like the idea adopted by the (in)famous TV Tropes Wiki of a Mohs Scale of Science Fiction Hardness. This gets away from simplistic binary distinctions and quibbles about whether we allow one “gimme” (e.g. FTL) or not.

Thanks to everyone who responded with reflexive revulsion to any comparison of Jack Chalker and Rosemary Kirstein. It was necessary, and Ms. Kirstein deserves far better comps. If only it didn’t take her a decade to write a book…

Re: The Steerswoman. It is not fantasy, because it is the terraforming of an alien world using semi-forgotten technology masquerading as magic and the hostile fantasy creatures are either robots (like the dragons) or indigenous inhabitants being wiped out by the terraforming process (which involves killsats). There is no need to be all coy and teasing about the reasons, the work has been out for quite some time now and has been openly discussed in multiple other forums.

When part of the joy of a work is the gradual revelation of things not at all as they seem, blithely spoiling it is scoundrelry no matter how old it is.

When the revelation, such as it is, is central to a recommendation with regard to the genre, then you cannot be coy about what it is. You’ve got to come out and say that the work being recommended is suitable to the list, and give the reason.

I would certainly second the inclusion of Egan on any such list. Several of his books (Incandescence comes to mind) are literally “playing with science”. And his not-quite-latest, Dichronauts, is based on some awesome physics- and geometry-tweaking.

@33, that was unnecessarily spoilery and I wish you would redact it. Sufficient to say the Steerswoman is not Fantasy and has hard science not only at it’s core but in all it’s limbs and flourishes.

I highly recommend them.

I have not yet read any of Greg Egan’s books (suggestions of where I should start are gratefully received). I am eagerly awaiting the release of The Best of Greg Egan.

But I read his sequential pair of novellas in Asimov, 3-Adica and Instantiation. I consider that story hard SF on the basis of its complex virtual reality core (I have a Ph.D. in computer science) and even on the rare and unlikely basis of its playing with (some members of) the Vienna Circle. Because the Vienna Circle conversations are about logical philosophy and the philosophy of mathematics, and I have degrees in (and love for) both mathematics and logical/mathematical philosophy, I came away almost imagining that Egan wrote that story specifically for me. Fortunately for readers unfamiliar with those two fields, those conversations are delightful decorations. Not so with the VR basis, which combines some fairly sophisticated understanding of current fundamentals with some arguably plausible great advances that may occur in the future.